Women comprise 58% of United Methodist members, but they are the minority when it comes to regional leadership.

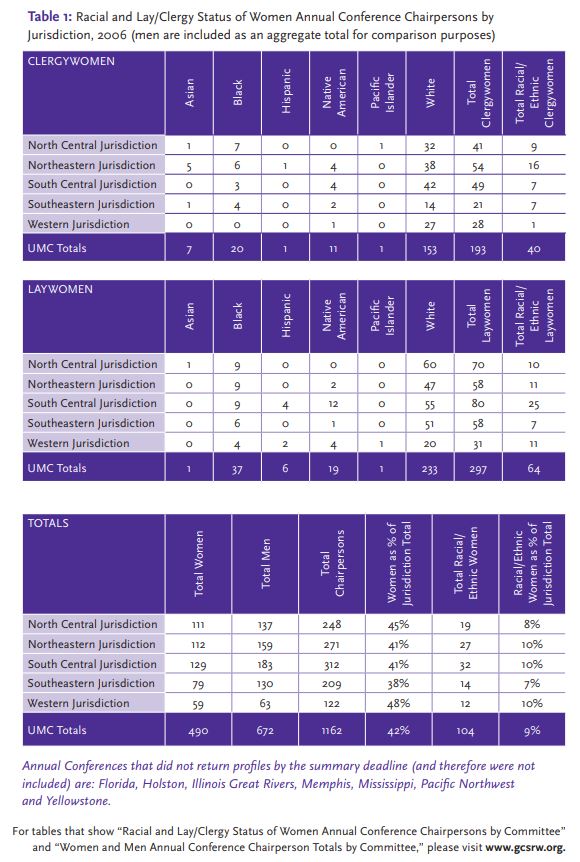

By Craig This and Elaine MayOf the 1,162 people named chairpersons of commissions, boards and committees in United Methodist annual conferences in the United States, approximately 490 (42%) are women. These numbers show phenomenal expansion of women’s leadership, especially considering that, just 35 years ago, women comprised just 20% of all voting members of church agencies.

Overall, each of the five U.S. jurisdictions has shown a steady increase in the number of women serving as presidents or chairpersons of missional and administrative committees, according to data compiled from the “Annual Conference Committee Chairpersons Profile 2006,” collected by the General Commission on Religion and Race and GCSRW.

The Western Jurisdiction has the greatest percentage of women chairpersons, with 48%. In the North Central Jurisdiction, women hold 45% of the committee chairs, and they hold 41% in the Northeastern Jurisdiction, 41% in the South Central Jurisdiction, and 38% in the Southeastern Jurisdiction.

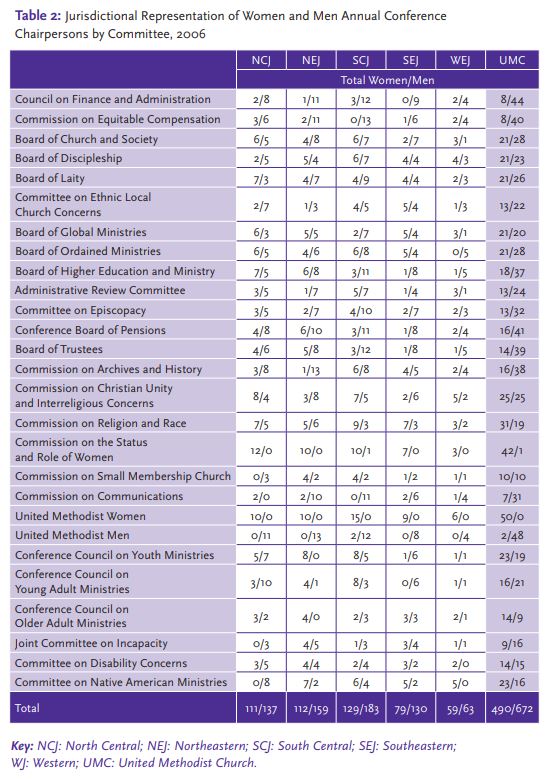

However, while the number of women leaders is on the rise, there is evidence that women are “pigeonholed” as heads of women’s ministry and advocacy, racial-ethnic concerns and youth ministry, and are still largely excluded as leaders of trustees, boards of pensions, and conference finance and administration.

In general, women are more likely to head annual conference commissions, boards and committees of (in order of frequency): United Methodist Women; COSROW; Commission on Religion and Race; Commission on Christian Unity and Interreligious Concerns; Commission on Youth Ministries; and Native American Concerns. These are often perceived as “soft” and “nurturing” ministries.

Men tend to chair at annual conference levels: United Methodist Men; Council on Finance and Administration; Conference Board of Pensions; Commission of Equitable Compensation; and the Board of Trustees. Most of these are more concerned with setting the decision-making and financial goals for the conference.

The decisions about who should chair what committee in the church seems to reflect how women and men are socialized and stereotyped. According to psychologist Carol Gilligan, men are socialized—and believe themselves to be—strategic, logical and concerned with creating and following strict rules and, as such, volunteer for—and are named to—positions where they can be judgmental and make yes-no decisions and measure how well the rules are followed.

Women, in general, are still socialized to put primary emphasis on building and nurturing relationships, so they are often asked to head committees concerned with team building, emerging ministries and strengthening interpersonal relationships.

Further, it can be argued that male-dominated entities are still considered the most vital to the “real work” of the church, while those headed by women are more likely to be considered less critical to our corporate spiritual and administrative life. Thus, those committees are subject to be restructured, discontinued, merged or dismissed.

And those mostly male-led administrative committees exert considerable control over those headed by women, since funding and influence of conference committees depends on how money and personnel are allocated, and which ministry groups are “important” and should have influence.

Women of color account for only 9% or 104 of the 1,162 persons serving as chairs of commissions, committees and boards across the annual conferences (see Table 1), and they are more likely than men and white women to chair committees related to their racialethic groups (e.g., several Native American women chair the conference Native American concerns committee). Racial/ethnic women are typically not assigned to those committees that provide overall leadership to the church or its annual conferences.

Yes, women in general are more visible than ever as leaders in United Methodist annual conferences. Still, this data demonstrates that gender and race often determine where women serve and how broad their influence will be. And since serving as an annual conference leader is often a requisite to election as a churchwide (general) agency leader, lack of gender and racial inclusiveness in annual conference agencies may spill over into general church leadership.

It would appear that the denomination still has work to do if our leadership circle is to reflect the racial and gender diversity of the nation and the world we seek to serve. White people cannot abdicate the anti-racism work of the church, just as men cannot leave anti-sexism work and caring for youth and children only to women. As men and women are represented more evenly on both administrative and missional committees, perhaps The United Methodist Church can become more balanced, creative, faithful and Christ-centered in all areas of our shared ministry.

Craig This is a faculty member of the Department of Sociology, Geography and Social Work at Sinclair Community College. Elaine Moy is assistant general secretary for finance and administration for GCSRW