Note: In March GCSRW will promote blogs for Women’s History Month, following the national theme of “Providing Hope and Healing.” We will feature several Methodist women who have been exceptional in the Church’s history of providing hope and healing while also emphasizing the importance of women’s work in the Church.

50th Anniversary blog series:

The work of the General Commission on the Status and Role of Women continues beyond its initial fifty years, but GCSRW’s existence does not constitute the whole of advocacy for women’s full participation in the life of the Church. As we continue to celebrate the pivotal role that GCSRW has modeled for Methodists, we also want to commemorate a few of the foremothers in Methodism who helped create a pathway for GCSRW’s institutionalization as a standing agency of The United Methodist Church. These women championed for equal acknowledgment of women in service and ministry to their congregations and communities and thereby empowered other women to follow their lead. Though structurally, women had limited official means to usher in a change in their status and role in the denomination, many women found significant ways to challenge the system through writing and speaking to Methodist women who sought their own expressions of ministry, while also seeking to confront social issues with a lens of intersectionality.

During Methodism’s first few decades, it faced a continual challenge: how to incorporate women into the life of the Church in the midst of a changing culture where women’s roles in society were evolving and expanding. Women sought the ability to have access to the same tools and responsibilities as men in Methodism, and one of the largest obstacles to remove became women’s right to preach. For years, while Methodism developed alongside democratic ideals of the Enlightenment, the leadership retained the post-Wesley leadership structure and relegated women to service and charity opportunities alone, despite women’s pleas that their calls were sound and their sanctification true. Many male Methodist preachers also advocated for women’s place in the pulpit. Although there was growing support for women to be licensed and ordained among their male counterparts, the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church allowed no women in their official capacity of leadership, even refusing women delegates among the laity in the legal structures of the denomination. Lay women finally received the right to election into annual conference delegations in 1904 by virtue of the 1900 General Conference legislation. For many conferences prior to women’s entry to the conference floor, the delegates entertained several proposals regarding women’s work and placed them in a specific committee dedicated to its oversight, of which the membership contained only clergymen. (1)

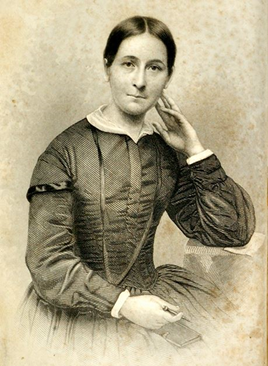

Phoebe Palmer (Courtesy: Common License)

The Holiness Movement to Drive Positive Transformation

The Holiness movement within Methodism called for several areas of theological adjustment and structural change, as they sought to inspire repentance and unleash the Holy Spirit across America for positive transformation. The Holiness movement adhered to Wesley’s belief in sanctification, in which a person could attain holiness of heart and life. Known as the mother of the Holiness movement, Phoebe Palmer wrote extensively about the doctrine of sanctification, and within her texts, while she felt that the clergy should be reserved for males alone, she shared her belief that women could be inspired by the Holy Spirit and “be allowed to preach and prophesy as did men similarly inspired.” Simultaneously, while the issues of women’s rights were debated within the Methodist Episcopal Church, women’s rights in America also emerged as a delicate topic, leading to the first woman's rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. The Holiness movement within Methodism sparked new conversations as America industrialized and modernized, but it shifted the theological foundations regarding sanctification, which provided space to increase the rationalization for women entering into ministry, including an experience-centered theology, a scripturally-based doctrine of holiness, a growing emphasis on the Holy Spirit at work, the freedom of experimentation, a central focus on sanctification with a partnering social critique, and an inclination toward sectarianism. (2)

In response to the denial of women’s ordination at the General Conference of 1880, Frances Willard wrote a scathing response in her publication Woman in the Pulpit and voraciously defended the right of women’s preaching. Following a “Do Everything” mentality, Willard saw no reason why women could not serve in every avenue of the denomination, cleverly suggesting that perhaps women could do some roles even better than men.

Frances Willard (Courtesy: Frances Willard House and Museum)

She claimed that the only reasoning for the denial of women’s right to the pulpit was because “men did not want to share power – especially sacred power – with women.” Willard not only criticized the General Conference’s denial of women’s ordination in 1880, but also the conference’s refusal to seat Willard and four other women who had been elected by their representative conferences. Willard’s composition “exposed in-depth the inadequate biblical exegesis of opponents of women’s public ministry,” as well criticizing the exclusive gendered language of the preachers. Willard emphasized that the source of church power and leadership came from Jesus Christ, not from Paul, arguing that expanding the office of clergy to women would empower the church and “give to humanity just twice the probability of strengthening and comforting speech, for women have at least as much sympathy, reverence, and spirituality as men, and they have at least equal felicity of manner and of utterance.” Willard gave significant progress to women in the denomination and women would soon earn greater rights within the Church. (3)

Driving Advocacy within the Church

By the end of the Gilded Age, women served in prominent roles of Deaconesses, a locally-based mission option for women to engage in justice ministries as single women. Many schools opened to train these women, including Scarritt College for Christian Workers (which eventually merged to become Scarritt-Bennett in Nashville). One such woman to be trained at Scarritt College was Thelma Stevens, who sought to be a Deaconess, but was denied the opportunity following her graduation in 1928 with a graduate degree. Instead, she focused her energies on advocacy issues that she felt were important, especially in regards to racism and misogyny in the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. Initially credentialed as a teacher from the Mississippi State Teachers College (now University of Southern Mississippi), she recalled her experiences of hearing students openly discuss the inhumane treatment of their Black family members. She committed herself to work to dismantle systemic racism in Mississippi and across the nation.

Thelma Stevens (Courtesy: Archives and History)

In 1940, she took charge of the Women’s Division’s Department of Christian Social Reform, which gave her the chance to approach issues from a national level, engaging Methodist Women in many events of the Civil Rights Movement, including the Freedom Rides, voter registration in Mississippi, and demonstrations in Selma and Montgomery. Not only did she lead the Division in protesting the segregated conference system of the 1968 United Methodist Church merger, but she also kept the Division ahead on decisions that were pro-women. She retired from the Women’s Division in 1968, but her work for justice continued. She helped establish the denomination’s Commission on the Status and Role of Women, as well as crafting position papers supporting the adoption of the Equal Rights Amendment. She joined with the efforts of the United Methodist Women’s Caucus and wrangled support from across the denomination to petition for the agency’s creation in 1972, writing the legislation to create GCSRW while also serving as the legislative strategies coordinator for the Caucus at the 1972 General Conference. Of the times, she claimed:

The year 1972 finds a great many women tired of waiting to be full and equal and responsible participants in the total life of the church. Small tokens and symbols of power are not enough in the Church of Jesus Christ! Of course the United Methodist Women’s Caucus had to be born and named. Its roots are centuries old but oppression, visible, intentional and unintentional has dwarfed both tree and branches. The objectives today are much the same but clothed in new faith and hope in a day when justice and personhood are the overreaching hope of peoples everywhere, including the majority group – women."

Additionally in her retirement, she provided consultation for the Ecumenical Women’s Institute in Chicago and Church Women United. (4)

Barbara Ricks Thompson, Guiding the Formative Years of GCSRW

Barbara Ricks Thompson (Courtesy: Archives and History)

With the institution of the General Commission on the Status and Role of Women in 1972, the agency needed a president. Serving in her first of many General Conferences as a delegate, Barbara Ricks Thompson was chosen not only to serve on the nascent Board of Directors but also to serve as the agency’s first president. A life-long Methodist, Thompson dedicated her life to social justice issues, even in her secular career with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Thompson brought a significant lens to the agency as a Black laywoman, focusing on the intersectionality of gender and race, which remained important to her throughout her service as president. In her first formative years, Thompson’s strategic issues became changing the culture to make it inviting for clergywomen and to increase the representation of laywomen within key roles of the denomination. Thompson claimed her proudest work as president of GCSRW was in evolving environments in local churches to make them more receptive to clergywomen appointments. Thompson formed a committee at GCSRW to be responsible for the agency’s addressing of racism and sexism, as well as creating interagency work for the task between GCSRW and the General Commission on Race and Religion. She mentioned in her retirement that this issue remained important in the 1970s because “there were not many women of color who were deeply involved in addressing women’s issues because they did not want to be perceived as diverting attention from issues of racism to issues of sexism.” In her parting words of her time at GCSRW, she emphasized, “The United Methodist Church needs both Commissions – Religion and Race and Status and Role of Women – to help in uncovering the manifestations of the ‘isms’ and in devising ways to overcome them. The ministry of these two agencies has helped the church to move forward, but there is still a great distance to go in achieving the multicultural community of faith I believe God wants us to be.” (5)

Thompson’s words describing her tenure at GCSRW still ring true. GCSRW remains necessary to continue the work of the UMC in having full participation of women in the life of the denomination and its local churches. These women bravely advocated for the marginalized peoples within the denomination, often giving the UMC incredible progress in some ways, but also displaying the stubbornness of centuries of Protestant patriarchy and hesitancy to evolve in egalitarian ways. Without the work of these women and so many others whose names many of us will never know, GCSRW would never be able to continue its work for the first fifty years of its existence. The future work of the agency and its contributors stand on the shoulders of many women who have desired women to be full and equal participants in the life of the UMC and never saw it come to fruition. As the agency celebrates its fiftieth year, we still desire the same and work diligently, knowing it may also be passed on to the next generation for fruition.

References:

(1) W.L. Harris and G.W. Woodruff, eds., Journal of the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, Brooklyn, N.Y. (New York: Nelson & Phillips, 1872).

(2) Carolyn De Swarte Gifford, The Defense of Women’s Rights to Ordination in the Methodist Episcopal Church, Women in American Protestant Religion, 1800-1930 4 (New York: Garland Pub, 1987).

(3) Carolyn De Swarte Gifford, The Defense of Women’s Rights to Ordination in the Methodist Episcopal Church, Women in American Protestant Religion, 1800-1930 4 (New York: Garland Pub, 1987); Paul Wesley Chilcote, The Methodist Defense of Women in Ministry: A Documentary History (Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, an imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers, Cascade Books, 2017).

(4) Alice G. Knotts, Fellowship of Love: Methodist Women Changing American Racial Attitudes, 1920-1968 (Nashville, Tenn: Kingswood Books, 1996); Thelma Stevens, “The United Methodist Women’s Caucus: From Evanston to Atlanta,” The Yellow Ribbon, May 1972, Women’s Caucus, New England Annual Conference, Boston University Theology Library Archives; Janet Allured, “Thelma Stevens,” in Mississippi Encyclopedia (Oxford, MIss.: Center for Study of Southern Culture, April 26, 2019), https://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/thelma-stevens/; Carolyn Henninger Oehler, The Journey Is Our Home (Chicago: General Commission on the Status and Role of Women, The United Methodist Church, 2015).

(5) Barbara Ricks Thompson, “From My Perspective,” The Flyer, Spring/Summer 1999, XIX, No. 2 edition, sec. Special Supplement Two, ResourceUMC.org, The Flyer Archives; Mark C. Shenise, “Guide to the Barbara Ricks Thompson Papers” (United Methodist Archives and History Center, January 15, 2019), African American Methodist Heritage Center, http://catalog.gcah.org/publicdata/gcah5924.htm.

Rev. Emily Nelms Chastain is a PhD student at Boston University, where she focuses on 19th and 20th Century American Christian History and the intersectionality of faith and gender. She earned her B.A. in History at the University of Alabama at Birmingham in 2007 and graduated with an M.A. Religion and M.Div. in 2019 from Claremont School of Theology. She's an ordained United Methodist Deacon in the North Alabama Conference, and entered academia after serving for 9 years within the United Methodist Church where she worked in Connectional Ministries. Emily served as a reserve delegate to the 2016 General Conference and as a delegate for the 2016 Southeastern Jurisdictional Conference. She has served on the GCSRW board since 2016.