By Erin Kane, GCSRW Director of Research and Monitoring

Over Independence Day weekend, I attended an event that included a reading of the Declaration of Independence. Many citizens become familiar with this document in their American history classes as children, but few know the declaration served as a model for an important document in women’s history 72 years later. The Declaration of Sentiments was signed on July 19, 1848, at the very first Women’s Convention in Seneca Falls, N.Y., an event convened to address women’s rights and women’s issues, most notably suffrage.

Methodism has a special place in the history of women’s suffrage. Anna Howard Shaw was not only one of the first women to be ordained by the Methodist Protestant Church, she also was an ardent suffragist. After her ordination in 1880, she would go on to promote women’s suffrage through grassroots leadership and later as the president of the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association from 1904-1915. She died just a few months before the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which won women the right to vote.

The United Methodist Church relies on a democratic voting process to elect leaders and determine doctrine in the Church regionally at annual conferences and more universally at General Conference. This quadrennium, for the first time, annual conferences had the option to choose General Conference delegates two years in advance of the event instead of one, so 11 U.S. conferences elected delegates in May or June this year.

From the Declaration of Sentiments:

“The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpation on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice. . . Having deprived her of this first right as a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides . . . After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it… He allows her in church, as well as State, but a subordinate position, claiming Apostolic authority for her exclusion from the ministry, and, with some exceptions, from any public participation in the affairs of the church. . .

Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation--in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of the United States.”

Click here to read the full Declaration of Sentiments

Some United Methodists have expressed concerns that early elections combined with a reduction in the overall number of General Conference delegates (to 850 from about 1,000) might result in less diversity among delegates. From a gender standpoint, however, that doesn’t appear to be the case in U.S. conferences so far.

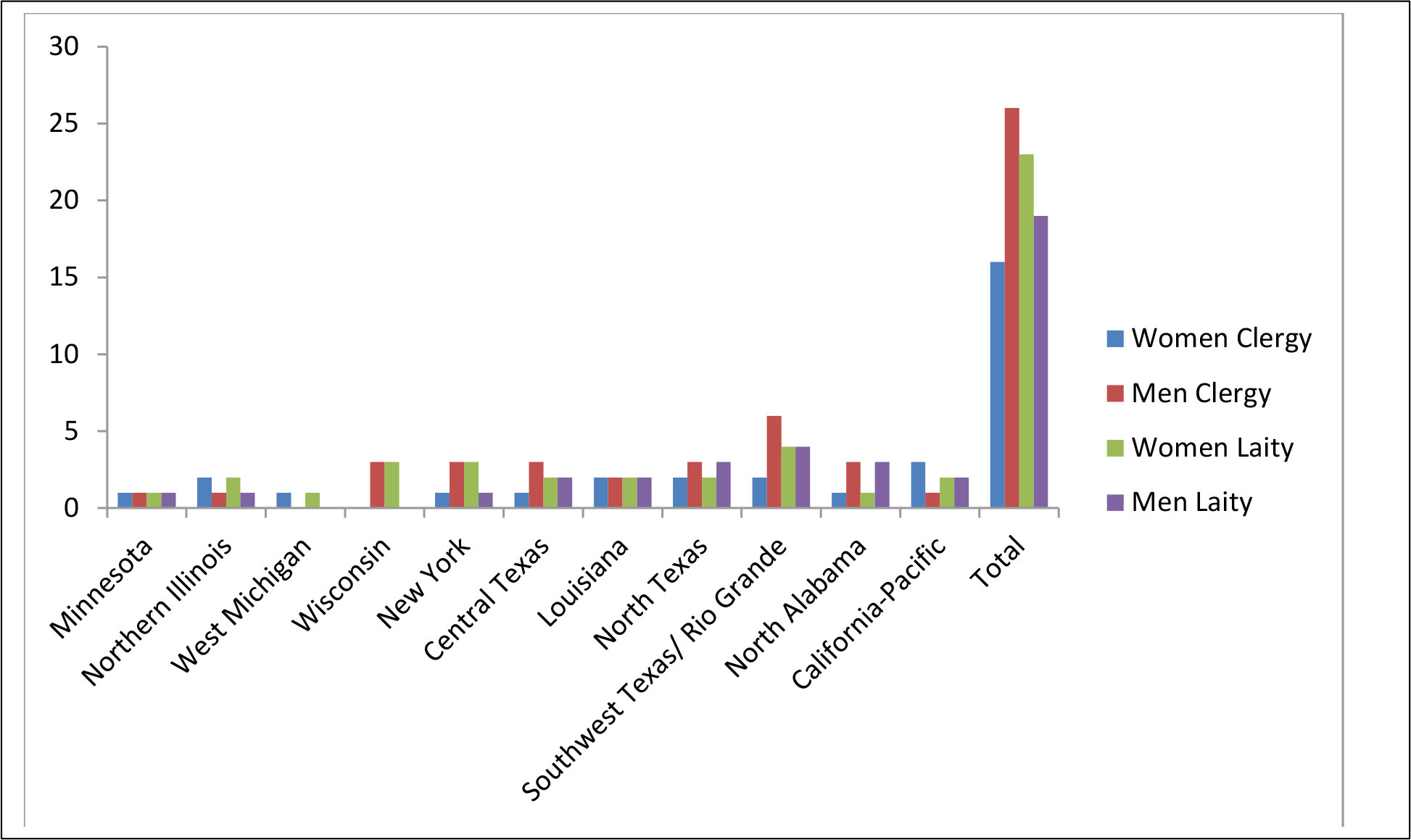

Gender Representation of 2016 General Council Delegates

In the 11 conferences, 39 of the 84 (46%) delegates elected are women, and 45 (54%) are men. More laywomen (23, or 55%) were elected than laymen (19, or 45%), and more clergymen (26, or 62%) were elected than clergywomen (16, or 38%). Interestingly, clergywomen were 25% of U.S. elders in 2011, the most recent figures available.

These delegates are nearly 10 percent of the total and represent a good start toward gender parity at General Conference 2016. The percentages compare favorably to the 2012 General Conference, when 44% of U.S. delegates were women, 44% of delegations were headed by women, and 39% of clergy delegates were women.

If the 2012 General Conference delegation were compared with countries globally in terms of gender representation within legislative bodies, it would rank among the top five. The congressional body of the United States lags far behind with only 18.5% women. (Women hold 20% of the seats in the Senate and 18.2% of the seats in the House of Representatives). This puts the United States at a ranking of 98th globally.

But why does women’s representation matter?

A recent study shows that citizens are more engaged when they have elected women. Both men and women constituents know more about their elected official’s voting record if they are women than if they are men. Citizens also hold the women accountable to those votes more frequently than they do the men.

Secondly, statistics have shown that U.S. Congresswomen are more legislatively effective than their male counterparts: “when compared to the average member of their party, women in the minority are about 31% more effective, and women in the majority are about 5% more effective than their male counterparts, all else equal.”

And lastly, as discussed in last month’s “Women by the Numbers,” gender diversity in representation matters for women and girls. Girls need to see women in positions of authority contributing to the decision-making and laws that affect their lives. Right now, bills about women’s issues have a 2.1% success rate and are more likely to have a high gridlock rate. And according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, it will take another 107 years for the US to achieve gender parity in Congress. That means that American girls won’t see a Congress that is reflective of the population until 2121 if women continue to be elected at current rates.

Discussion

Who in your Annual Conference is running for election to General Conference?

Are women in your Annual Conference being encouraged to run?

How would electing more – or fewer – women delegates affect your Annual Conference?

Learn more

If you’re considering a run for 2016 or 2020 General Conference delegate, check out our step-by-step guide here.

You can read more about Anna Howard Shaw (and other women in Methodist history) in the gallery on our website as well.

If you want to respond to these discussion questions, or if you have an idea for an article or research, email Erin Kane, our director of research and monitoring.